Ayela Spiro, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

Fibre, fibre, everywhere…

The recent Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) draft report on carbohydrates [1] recognised that despite a substantial evidence base for the health benefits of fibre-rich diets, generally in the UK, we do not consume enough fibre, so need to increase our intake significantly.

What is fibre?

Dietary fibre, found naturally only in foods of plant origin, is the common name for carbohydrate components occurring in foods that are not digested in the human small intestine. Fibre falls broadly into two main groups, completely fermentable (soluble) and partially fermentable (insoluble) [2, 3]. Fibre-rich foods typically contain a mixture of both, but in different proportions (Table 1). It is important to include both in the diet, as each group confers health benefits through different mechanisms such as bulking, viscosity and fermentation.

Fibre and digestive health

While different fibre types can have a range of health effects, the popular conception of fibre, colloquially referred to as ‘roughage’, is that its health benefit lies principally in bowel regulation, particularly in the prevention of constipation.

A diet low in fibre is also associated with diverticulitis [3] where the bowel wall becomes inflamed and ultimately damaged. Sources of partially fermentable or insoluble fibre help to prevent constipation by:

- increasing faecal wet weight

- softening stools and increasing their bulk

- increasing the rate of faecal transit, allowing faster movement through the digestive tract [1]

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance suggests advising adults with constipation to increase their fibre intake, ensure adequate fluid intake, and to take exercise [4].

Fibre and risk of chronic disease

Other health benefits of fibre-rich diets are increasingly being recognised [1]. Research has suggested that higher consumption of dietary fibre is associated with reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer.

However, the mechanisms that underlie the health benefits of fibre have not been fully elucidated. Soluble fibre forms a viscous gel when mixed with liquid in the small intestine, and can slow both gastric emptying and the rate of glucose absorption [3]. This may help regulate blood glucose levels, which is particularly important for people with type 2 diabetes and in women with gestational diabetes.

The delay in gastric emptying may also result in promoting satiety (feeling fuller). Furthermore, foods high in fibre tend to have a low energy density, again helping to reduce hunger and promote a sense of fullness. Fibre may therefore be able to play a key role in weight management.

Much of the research into the cholesterol- lowering effect of fibre has used oat beta-glucan, a soluble dietary fibre that is found in the endosperm cell walls of oats (and barley). Studies suggest a daily intake of at least 3g may reduce plasma total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels by around 5% in those with high or normal blood cholesterol levels [6]. The most commonly proposed mechanism to explain the cholesterol-reducing effects of soluble dietary fibre is that it can bind with bile acids in the small intestine preventing their reabsorption, leading to an increase in their excretion. The loss of bile acids in the stool stimulates the liver to increase cholesterol uptake from the circulation to replenish the bile acid supply. As a result, concentrations of serum total and LDL cholesterol are reduced.

There is also some evidence that a high dietary fibre intake may protect against colorectal cancer [7]. Suggested mechanisms have included increasing the transit time of waste products through the gut. In addition, fibre reaches the colon largely undigested where it is used as a substrate for bacterial fermentation. This may increase the number of beneficial gut bacteria and help to prevent the multiplication of abnormal colorectal cells.

The significance of how dietary factors such as fibre can modulate gut microbiota, and how this may impact areas such as immunity and allergy [8], is an area of growing research and one that might have implications for future dietary recommendations.

How much fibre do we need?

The government currently recommends that adults eat at least 18g/d of fibre (measured as non-starch polysaccharides, [NSPs]), although this may be increased in response to the SACN carbohydrate report [1]. On average, UK consumption is much less; about 14g per day. For the majority of the population, increasing fibre will be beneficial; however, some clinical conditions, for example diarrhoea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), require careful management of fibre intake [9].

We must also be aware that whilst evidence suggests a protective effect of eating a diet rich in dietary fibre on chronic disease, it is unclear whether this is always a direct effect of the fibre or whether it is because a high fibre intake is a characteristic of a healthier diet and lifestyle. In other words, it may also be that people who eat plenty of fibre follow other dietary advice such as to eat less fat, eat plenty fruit and vegetables, drink plenty fluid and do more exercise.

BNF Online training course for practice nurses on dietary fibre

To learn more about fibre, including practical examples of foods that nurses can recommend to increase fibre intake amongst their patients, the British Nutrition Foundation provide an online training course on this topic. This three-module course designed specifically for practice nurses, aims to explain the science behind the different types of dietary fibre, current UK intakes of fibre and the different foods that provide fibre in the diet. It also describes the health benefits of a fibre-rich diet, and practical tips that patients can follow to increase their fibre intake, including case studies. Each module has an end test, providing feedback on progress. This course takes approximately 1-2 hours to complete, but can be done at the pace required, and is available at: http://www.nutrition.org.uk/online-training-sp-221/training/courses.html.

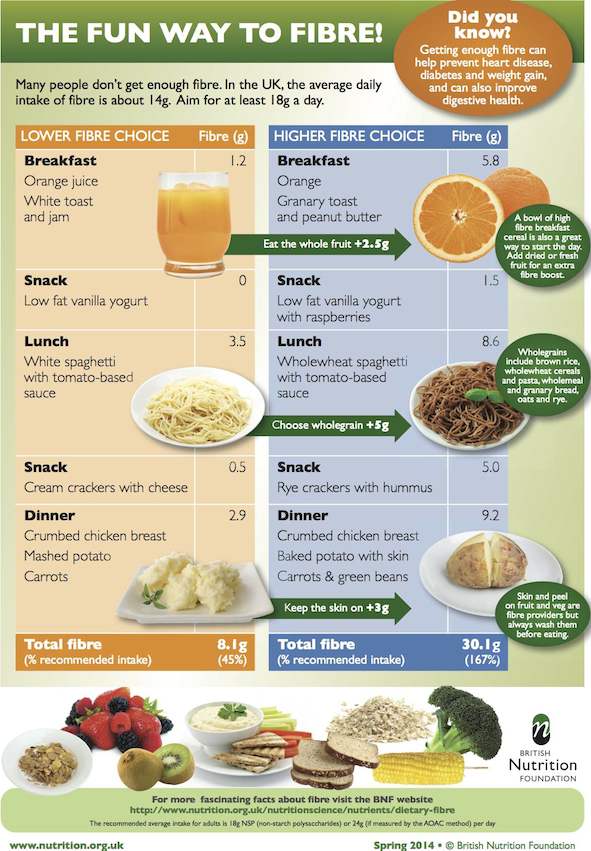

Further simple tips for patients to increase fibre in the diet can be found in the BNF Poster ‘Fun Ways to Fibre.’ See Below or visit http://www.nutrition.org.uk/attachments/651_Fun%20to%20Fibre%20A4%20Poster.pdf

BNF is also running a mini conference New Frontiers in Fibre on 29th January 2015 in London. Further details are available at: http://www.nutrition.org.uk/bnfevents/events/new-frontiers-in-fibre.html

..despite a substantial evidence base for the health benefits of fibre-rich diets, generally in the UK, we do not consume enough fibre, and need to increase our intake significantly.