Ovarian Cancer: What you need to know

Authored by Ovarian Cancer Action

What is Ovarian Cancer?

What is ovarian cancer?

Ovarian cancer occurs when abnormal cells within the ovary start to multiply uncontrollably creating a tumour that can spread to other parts of the body. There are three broad types of ovarian tumours and these are classified according to where in the ovary they originated.

- Epithelial ovarian tumours are the most common type of ovarian tumour accounting for 85-90% of all ovarian tumours. Most are malignant and they tend to affect women over the age of 50. Epithelial ovarian tumours originate from the cells that line the ovaries and there are several sub-types which include: serous, endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, transitional cell and undifferentiatied. In addition, there are cancers that are very similar to epithelial ovarian cancer, most notably, primary peritoneal cancer. It is sometimes referred to as extra-ovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma or serious surface papillary carcinoma. This type of cancer is rare and develops from the cells that line the pelvis. It has the same symptoms as ovarian cancer and is diagnosed and treated in the same way

- Germ cell tumours originate in the cells within the ovary that develop into eggs. This is a rare tumour that accounts for 5-10% of ovarian tumours and they tend to occur in younger women (mostly in their 20s). Most germ cell tumours are non-cancerous and 90% of cases can be successfully treated

- Sex cord stromal tumours begin in the connective cells that hold the ovaries together. They can affect all age groups. Most of these tumours are either not cancerous or are very slow growing and they account for 5% of all ovarian tumours

Grades and Stages

As well as being classified by type and sub-type, ovarian cancers are also staged based on how aggressive they are and this is determined by whether the cells look similar to normal cells and how fast they grow.

- Stage 1; considered to be early stage and this is where the cancer is confined to one or both ovaries. They tend to look very similar to normal tissues cells and don’t grow very quickly

- Stage 2; occurs when the cancer is found outside the ovary or ovaries, but has spread no further than the pelvic region (uterus, bladder, lower intestine). They grow moderately fast

- Stage 3 ovarian cancer; spread beyond the pelvis into the abdominal cavity (but not the liver) and/or to nearby lymph nodes. Cells look very different to normal tissue cells, grow very quickly and grown in a disorganised way – these are aggressive cancers

- Stage 4; cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body such as the liver, lungs and brain

Risk Factors

Ovarian cancer is a fairly rare condition with a woman’s lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer being 1 in 54, but there are factors that increase a women’s risk of developing ovarian cancer.

The two most important risk factors for ovarian cancer are age and family history. The risk of ovarian cancer increases as a woman gets older with over 80% of cases occurring in women who are over the age of 50. Another important risk factor is family history with 10-15% of cases occurring in women who have a family history of cancer. This increase in risk is due mostly to the inherited genetic mutations BRCA1 and BRCA2. Additionally, the inherited genetic mutations linked to hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, formally known as Lynch Syndrome) increase risk of hereditary ovarian cancer.

The BRCA gene mutations are associated with breast and ovarian cancer with women having a BRCA gene mutation having a 35-60% chance of developing ovarian cancer and an 80% chance of developing breast cancer.

HNPCC is linked to bowel, ovarian, womb, stomach and endometrial cancer and women with the mutations linked to HNPCC have a 10% chance of developing ovarian cancer.

This means that women who are more likely to developing ovarian cancer are:

- older women

- women with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer

- women with a family history of ovarian, bowl, womb, stomach and endometrial cancer

It’s important that women who fall into these categories are aware of their risk and are given appropriate advice. Older women should be aware of the signs and symptoms and visit their doctor if they have any concerns and ask for a CA125 blood test to rule out ovarian cancer. Women with a family history should make detailed notes about members of their family who have been affected by cancer, what type of cancer and the age of diagnosis and take this with them to their GP and discuss what this might mean about their risk of developing of ovarian cancer. Additionally, they can speak to their GP about whether genetic testing is appropriate to determine whether they have an inherited genetic mutation (BRCA mutation or HNPCC). For women with a significant family history a referral to a genetic clinic is recommended so that women can have a consultation with a genetic counsellor. It’s important for women to know whether they have an inherited genetic mutation as steps can be taken to reduce risk such as preventative surgery.

Additionally there are other factors that slightly increases risk of ovarian cancer. These include being obese, not having children, having endometriosis and use of HRT. A women’s risk decreases with each pregnancy she has and breastfeeding also lowers risk as well as the contraceptive pill.

The Symptoms of Ovarian Cancer

If a woman presents with the following symptoms on a persistent and frequent basis, more than 12 times a month, especially if she is aged over 50 then ovarian cancer should be suspected and ruled out.

- persistent abdominal distention or “bloating”

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- early satiety and/or loss of appetite

- increased urinary urgency and/or frequency

In addition, a woman may also present with the following less common symptoms:

- back pain

- changes in bowel habit (diarrhoea or constipation)

- fatigue

The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be challenging to recognise because they are similar to the symptoms of a number of non-serious conditions. The key features that differentiate ovarian cancer symptoms from those of non-serious conditions are they are :

- persistent – they last for at least 12 days a month

- unusual and new to the patient; and they

- progressively get worse

Diagnosing Ovarian Cancer

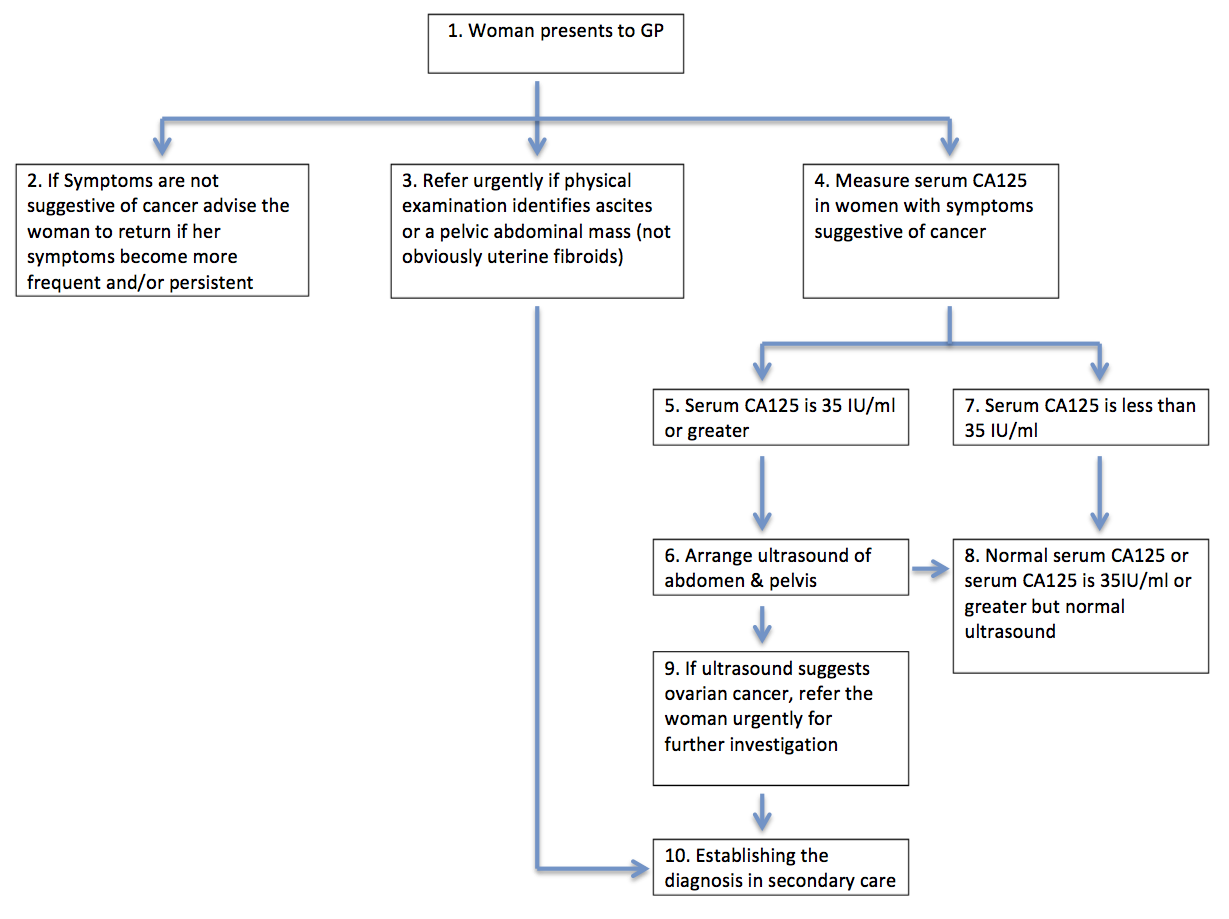

There is no screening test for ovarian cancer so diagnosis is based on symptoms recognition. If a woman experiences the symptoms of ovarian cancer and a physical examination suggests ovarian cancer due to the presence of an abdominal mass or ascites then NICE suggests an urgent referral to secondary care for suspected ovarian cancer (http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/ovarian-cancer#path=view%3A/pathways/ovarian-cancer/ovarian-cancer-detection-in-primary-care.xml&content=view-index).

If a woman has symptoms but a physical examination doesn’t reveal ascites or an abdominal mass then a blood sample should be taken and serum CA125 levels measured. If her CA125 level is over 35 IU/ml then an ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis should be conducted and if that suggests ovarian cancer an urgent referral should be made (Figure 1).

Treatment and Support

Treatment for ovarian cancer depends on the stage and type of the disease. For most women treatment will involve surgery followed by chemotherapy, but for women with advanced disease their treatment may begin with chemotherapy followed by surgery and another course of chemotherapy.

Surgery for early stage ovarian cancer usually involves the removal of the affected ovary and fallopian tube (oophorectomy and salpingectomy) but for more advanced disease surgery may involve removal of:

- both ovaries, the fallopian tubes and the uterus (this is known as a total hysterectomy)

- nearby lymph nodes and surrounding tissue

- the omentum (the fatty tissue covering the intestines)

- any cancer that has spread into the abdominal cavity

- the appendix

The second step of treatment, chemotherapy, may not be required for some early stage ovarian cancers, but on the whole most patients will require chemotherapy which usually starts after surgery. The two most common treatments for epithelial ovarian cancer at first presentation are:

- Paclitaxel with carboplatin; or

- Single agent carboplatin

Germ cell ovarian cancer is most commonly treated with a combination of the drugs bleomcyin, etoposide and cisplatin (referred to as BEP).

Sex-cord stromal ovarian tumours are not usually treated with chemotherapy. If chemotherapy is required, the drug combinations used are either:

- carboplatin with paclitaxel; or

- bleomcyin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP)

Chemotherapy patients are monitored regularly to check how well the treatment is working. Treatment is monitored in several ways:

- regular CA125 blood tests

- CT or ultrasound scans

- periodic blood counts

Once the full course of chemotherapy has been completed, patients will have check-ups every three months, and then every six months if they are still cancer free.

If a patient is cancer free after ten years (or five years for early stage ovarian cancer), they are considered to be in remission and will no longer need regular check-ups.

Recurrence

One of the major challenges with ovarian cancer is recurrence. Seventy percent of ovarian cancer patients will experience a recurrence of their disease despite achieving remission. A recurrence may occur because residual cancers cells, which were undetectable after treatment, remained or some of the cancer cells were resistant to the platinum-basedchemotherapy or became resistant over time and these remained after treatment. There are three types of recurrence:

- local recurrence – this is where the cancer recurs in the same location as it started

- regional recurrence – in this situation the cancer recurs near where it originally started

- distant recurrence – this occurs in an organ or tissue in another part of the body such as the liver, lungs of brain.

In ovarian cancer, recurrence is likely to be regional and distant as the ovaries will have been removed during treatment.

Treating recurrent ovarian cancer is challenging and options can be limited especially if the recurrence is due to chemotherapy resistance. Those patients who have not developed chemotherapy resistance will be treated with platinum-based combination chemotherapy; this is treatment that includes the drugs cisplatin or carboplatin. If the patient’s cancer is resistant to these drugs than their oncologist will explore other options, this may involve entering the patient into a clinical trial.

The Impact of Ovarian Cancer

A diagnosis of ovarian cancer can be devastating, significantly affecting the quality of life of patients. Women not only suffer from the consequences of the disease but also have to live with the long-term impact of its treatment.

Most women diagnosed with ovarian cancer are diagnosed at stage 3 or 4 and this means that the majority of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer have a poor prognosis. This has a significant impact emotionally with patients experiencing high levels of fear and anxiety. Even after a seemingly successful course of treatment there is still fear and anxiety due to the possibility of a recurrence. This creates a sense of uncertainty about the future and this uncertainty is difficult to live with. This fear and anxiety is not just experienced by patients but family and friends too.

The treatment of ovarian cancer, depending on the stage at diagnosis, involves surgery followed by six rounds of chemotherapy. Surgery leads to a loss of fertility with many women going into premature menopause, with its resulting effects, and chemotherapy can cause a number of short and long term effects.

For an ovarian cancer patient, their condition affects every aspect of their life – their relationships, work, family life and social life. And, in many cases there can be additional challenges due to stigma, cultural insensitivity, a feeling of isolation and in some cases unaddressed psychosexual issues.

Conclusion

Addressing these issues is a challenge and a key part of this is ensuring that ovarian cancer is diagnosed as early as possible to improve survival rates and to lessen the impact of advanced disease. Organisations like our charities Ovarian Cancer Action and the National are working tirelessly to address these issues by funding world class scientific research across the spectrum from early diagnosis through to surgery, new treatments and survivorship. We also campaign to ensure women and healthcare professionals know the risk factors, symptoms and treatment options to enable informed and rapid action.Fundamentally we demand that every woman should have the best treatment available.

More Information

Ovarian Cancer Action

0207 380 1730

National Forum for Gynaecological Oncology Nurses

Annie's Experience

Annie Chillingworth, 50, lives with her husband and children in Sherborne. She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2009.

Annie has a long family history of breast and ovarian cancer and, because of this history she had yearly breast checks from the age of 27. For a long time she suspected she may carry a faulty BRCA gene but didn’t feel informed enough to push for testing.

Annie said: “From the first time I became aware that they’d identified the BRCA gene in my family I asked at my check-ups if it would be possible to be tested. But the answers were always unclear, blurred. I also asked about the link between ovarian cancer and breast cancer, again they were unclear about the need for screening.”

In the spring of 2008 Annie visited her GP with a lump in the side of her abdomen. “I mentioned that I had a family history of breast and ovarian cancer but in a dismissive, embarrassed way. I was worried that they’d think I was being dramatic,” she said. Her GP said it was likely IBS and no action was taken.

In the summer, Annie felt bloated. She needed to go to the loo frequently and was experiencing intermittent bleeding. Heading back to her GP she again mentioned her family history but her GP thought cancer was unlikely. When, in December, Annie experiences a swollen abdomen, she is finally sent for a scan.

Annie was diagnosed with stage 3 ovarian cancer in March 2009. “A part of me felt like my diagnosis was inevitable, given my family history,” she said.

“Another part of me just wanted to put my fingers in my ears, bury my head in the sand. But mostly, for a long time after I was diagnosed I felt very angry that I had been so well positioned to catch my ovarian cancer early. If I had been better informed, I could have insisted on being screened for ovarian cancer too. If I had known my BRCA status I could have taken preventative measures.”

After having her womb removed in March 2009, Annie faced more surgery after it was confirmed that she did, indeed, carry a BRCA gene mutation. She went onto have a preventative double mastectomy in July 2010.

Annie said: “I felt annoyed with myself that I hadn’t been more assertive in trying to access screening or trying to find out if I had the gene fault. But it made me determined that my children and wider family would not slip through the net. It filled me with a desperate need to find out if my children carried the faulty gene.

“As time has passed and we have found that my daughter has not got the genetic fault I feel great relief. My boys both want to find out when they are 18. It has been a part of all of our lives for so long that it doesn’t seem so terrible now, just something to be dealt with. Knowing we have a family history has given us some control back.

“There are days when I still feel angry. And I can’t help but wonder whether the years of chemo and heartache could have been avoided had I known my BRCA status.”

“Mostly though, I am grateful to still be here.”