Births, Babies and Boobies

Sue Smith, RGN, RHV (Rtd)

Women stayed in bed for three days after the birth (even after a normal delivery). Bedpans were required, and it was the junior nurses' job to give a jug douche after every bedpan.

I seem to have written about death, so it's time to take my thoughts to life's beginnings.

I remember being quite upset when I learned that my mother, although a wonderful mother, had been distraught when she found she was pregnant with me. I later realised that at that time her brother was stranded on the beaches of Dunkirk and her husband with whom she had only been able to spend a few 48-hour leaves in the six months of their marriage, was in the RAF and stationed 300 miles away, so she was living with her parents for the duration of WWII, working and experiencing nightly bombings.

It was Spring 1940 and the fear of invasion was both real, and possibly imminent. The German army was only 21 miles across the Channel from England's south coast. Not the time she would have chosen to bring a baby into this frightening world at war. However, I was determined that I would be a welcoming mother from moment I knew I was expecting a baby.

My first experience of birth was on the Maternity ward during my first year as a student nurse at Westminster Hospital, London. It was the hot summer of 1959 and I was eighteen. Back in those rather prudish post-war days, before the 'enlightenment' of Flower Power, Carnaby Street fashion, and the Beatles. I remember being amazed and impressed by the whole birth process.The arrival of each new baby complete with fingers, toes and a lusty cry never ceased to seem like a miracle.

Many local people (in London's Victoria area) had home births attended by the district midwives based on the Maternity ward. They wore blue dresses with red belts (staff nurses and sisters had dark blue belts) and hats. Think "Call the Midwife" and you're there!

Jennifer Worth's memoirs of her time in Poplar relate to just a couple of years before I saw my first birth. In both places women were delivered on their side, with one midwife holding the mother's upper leg to keep it out of the 'action area'. Newton's law of gravity had obviously not been applied to childbirth in the 1950s and early 60s. As nurses and midwives at that time were predominantly childless it never seemed to occur to them how archaic this practice was.Hospital births were mainly midwife-led, and husbands were definitely not welcome!

Antenatal classes for the women, (maybe with one 'Father's night') at that time covered the mechanics of the birth, how to bath a baby, how to sterilise glass feeding bottles and prepare bottle feeds from powdered baby milks and boiling water. Breast-feeding may have received a brief mention, but it was incidental.

Women stayed in bed for three days after the birth (even after a normal delivery). Bedpans were required, and it was the junior nurses' job to give a jug douche after every bedpan. Just writing this in 2016 shocks me! I didn't feel old until writing this. It is not actually feeling old (I don't!) it is realising just how much things have changed during my adult life.

I don't know what the statistics were for DVTs in the maternity wards, but staying in bed for three days sounds more Jane Austen than Primary Care Nursing Review!

Every four hours we carried trays of Pyrex jugs holding bottles of prepared baby milk, into the ward. The expectation was that 95% of the mothers would be bottle-feeding. I guess the birth rate was lower, and nurses and midwives more plentiful. Women had fewer career choices in the 1950s.Research into the perils of immobility was in its infancy, as was research into the importance of parent-baby bonding and the benefits of breastfeeding.

Truby King's advice ruled: this meant four-hourly feeding--with a bottle and formula milk, and more controlling parenting 'routines'. No consideration that the baby's needs may not fit this regimen. Child Welfare reformer Sir Frederick Truby King was credited with drastically reducing infant mortality in his native New Zealand, so his methods were praised.

To me this shows just how every generation breeds its own 'experts'--according to the needs of the time. And with the intention of improving outcomes. The late 20th century saw 'research-based-practice' become the modus vivendi in all realms of health and child care - but unfortunately students were not always encouraged to look at the funding of the 'research' and to consider if commercial interests benefited from the research (that discussion is for another column!)

Back to babies! I had married at the end of my nurse training and left a year later to have our first baby. Born, of course, at Westminster in 1963. I had been to ante-natal classes where they proposed this new idea of 'psychoprophylaxis'. This encouraged women to lose their fear and doubts about childbirth, and to see labour as a series of contractions that could be managed. Labour 'pains' were seen as triggers that could stimulate positive actions, and women were encouraged to relax between contractions to prevent tensing up with anxiety.

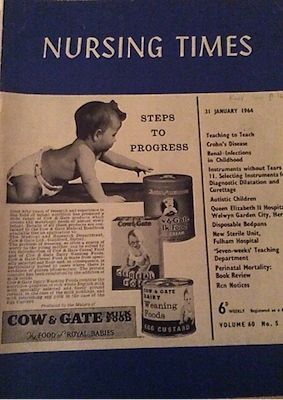

My first 'publication' was a letter to Nursing Times (31 January 1964) (Figure 1) praising this preparation for childbirth that I had found very helpful. Finding this NT tucked away for 50 years, I notice that there is an advertisement for baby milk on the cover (Figure 2). Hardly surprising then that I was expected to bottle feed. As I insisted on trying to breastfeed, I received little help and as my first baby was considered 'very small' at 5lbs 11oz, he had to be weighed before every feed--and weighed again afterwards. If he hadn't had enough from me I had to 'top him up' with formula.

Hardly conducive to successful breastfeeding. Fortunately this attitude has changed markedly over the past 50 years. Even by the time my daughter was born, in 1970, the midwife was very encouraging and I fed my daughter successfully for nine months. Only using boiled cow's milk if some weaning foods needed to be mixed with milk.

Although I was delivered on my side for my first baby, the practice had changed three years later when my second son was born. I was half sitting (gravity was a great help!) --and my husband was present!

By the time my grandchildren were born, breast was definitely seen as best. How fashions change! I just wonder what will be the norm by the time any great-grandchildren arrive.

I am sure you all have your own stories to tell and I guess the moral is for us to understand that technology, fashion, personal and professional interests, research and commercial or media interests all move in great waves. It is what makes living our lives (and our individuality when we get the chance to express it) so absolutely fascinating.

Newton's law of gravity had obviously not been applied to childbirth in the 1950s and early 60s