Developing criteria for wound dressing selection

Legg, D. MCIPS, Procurement Consultant, Procure Analytics Ltd.

Parker J. RGN, Tissue Viability Lead Specialist Nurse, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King’s Lynn

Editors Note:

In the interests of transparency, PCNR acknowledges that a version of this article has previously been submitted to a different journal, and that Deborah Glover provided advice to the authors.

Fool's errand?

Anyone who willingly reinvents the wheel is either a tad foolish or short of something to do. The majority of the professionals working in the NHS are neither, yet on average every two to three years, they do exactly that. In the process of reinventing this wheel, time and resources are wasted.

What is this reinvention? The development and/or review of an organisations’ wound care formulary (WCF). Such reviews are usually driven either by the desire to improve patient outcomes by ensuring clinicians are utilising appropriate dressings for the case in hand, or by procurement to seek unit cost savings.

With both a proposed National Wound Formulary and a set of dressing criteria standards being developed at national level, this article outlines the pre-emptive development of a dressing criteria tool.

Developing dressing usage criteria

A plethora of wound management products exists; from foams to films, from alginates to negative pressure devices, each category contains myriad variations on a theme. This presents healthcare professionals with a massive choice of products and the potential for inappropriate use with associated costs. To rationalise this choice, many organisations have developed wound management/care formularies (WMFs), with a limited number of products from each category of dressing. However, WMF groups have to be cognisant of the fact that along with the desire to improve patient outcomes by ensuring clinicians are utilising appropriate dressings, procurement managers will seek unit cost savings.

Realistically, developing a WMF isn’t a straightforward exercise, no matter how skilled the members of the wound formulary group (WFG). In the process a number of points have to be considered:

1. Cost and cost benefit of dressing

The most challenging aspect; WFG members need to know cost of each dressing and whether or not this represents ‘value for money’. This is usually demonstrated by evaluating wear time, absorption capability, and patient comfort (if the patient is happy and pain free, concordance will improve). If dressing ‘a’ is more expensive than dressing ‘b’, but is more absorbent (for example), the wound heals faster, patients see better outcomes, and are discharged quicker, then it is more cost efficient.

However, this is a difficult point to argue with non-clinicians, who may only consider the ‘bottom-line’, i.e. the unit cost. Cost effectiveness can be demonstrated; for example, Guest et al [1] undertook a comparative study which aimed to determine the clinical outcomes and relative cost-effectiveness of using three compression systems for the treatment of venous leg ulcers in clinical practice. Despite the limitations of the study, of the three systems used, the second most expensive in terms of unit cost, resulted in a lower six-monthly cost to the NHS and more positive quality of life indicators than the other two compression systems. As it had a longer wear time, and thus required less frequent changes, saving on nursing time too.

2. The clinical benefit of each dressing

The WFG need to consider the clinical benefit of each dressing; for example, absorption/rehydration/debridement properties, pain management properties, and patient comfort/acceptability (for example, compression may be clinically the best treatment for VLUs but non-compliance makes it an expensive option).

3. The number of dressings from each category to evaluate

With tens, if not hundreds to choose from in each category (foam, hydrocolloid, film, alginate, etc), how do you decide which ones to evaluate and why? Are decisions based on appropriate research, or on the ‘flavour of the moment’; how do you ensure you are not being too selective in your choice?

4. Criteria to use for evaluating each category of dressing

The criteria may need to vary according to the genre. Can you evaluate all dressings in the genre using the same criteria? Do these criteria meet those required by clinicians and procurement?

Innovation

In addition to considering how to implement the recommendations of Lord Carter’s NHS Procurement and Efficiency Board 2015 report [2], the nurse author (JP) and a colleague were considering how to address issues that had arisen when considering the review of their respective formularies. These included:

- Time: It had taken two TVNs over a year to develop a new clinically and cost effective formulary; it had involved numerous product evaluations and submitting a business case. Consequently, the idea to develop a criteria for a dressings formulary that would “satisfy” the needs of the clinicians, procurement and the patients was born

- Acute vs community trust formularies: The acute and community sectors had differing needs and ideas about what should be included. Considerable off-formulary spending in the community which required investigation was noted - was it because individual nurses liked using what they were used to, or because they needed training in new products, or because the products they were choosing were actually better? They needed a formulary that would meet the needs of both sectors to improve compliance.

It was postulated that they could improve the way they selected dressings in order to save time and resources to ensure that the most appropriate dressings would be available. After a discussion at the European Wound Management Association conference in 2015 with the second author DL, a procurement specialist with experience of working with NHS Wound Formulary Groups, they came together to draft a set of generic criteria for dressing selection.

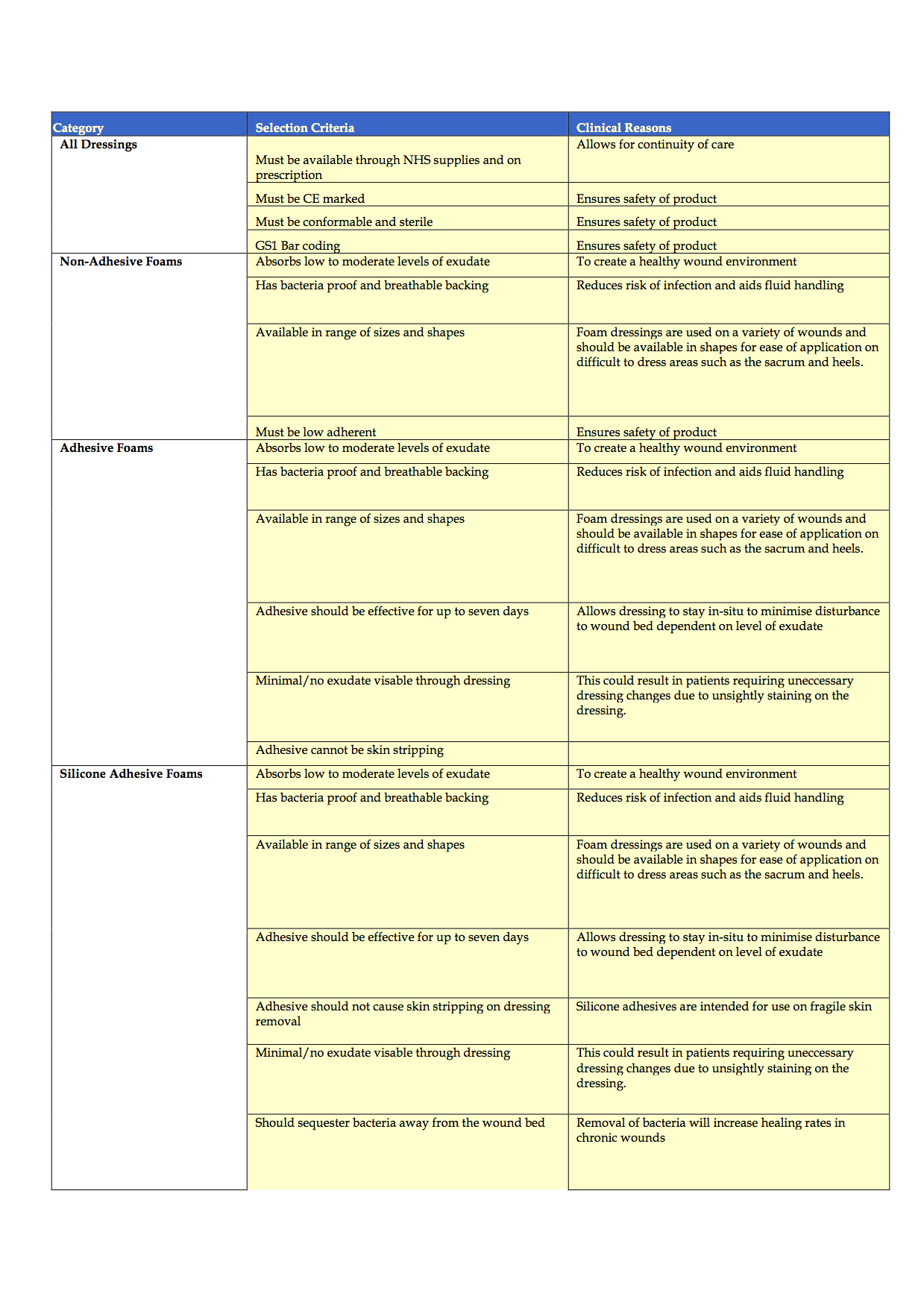

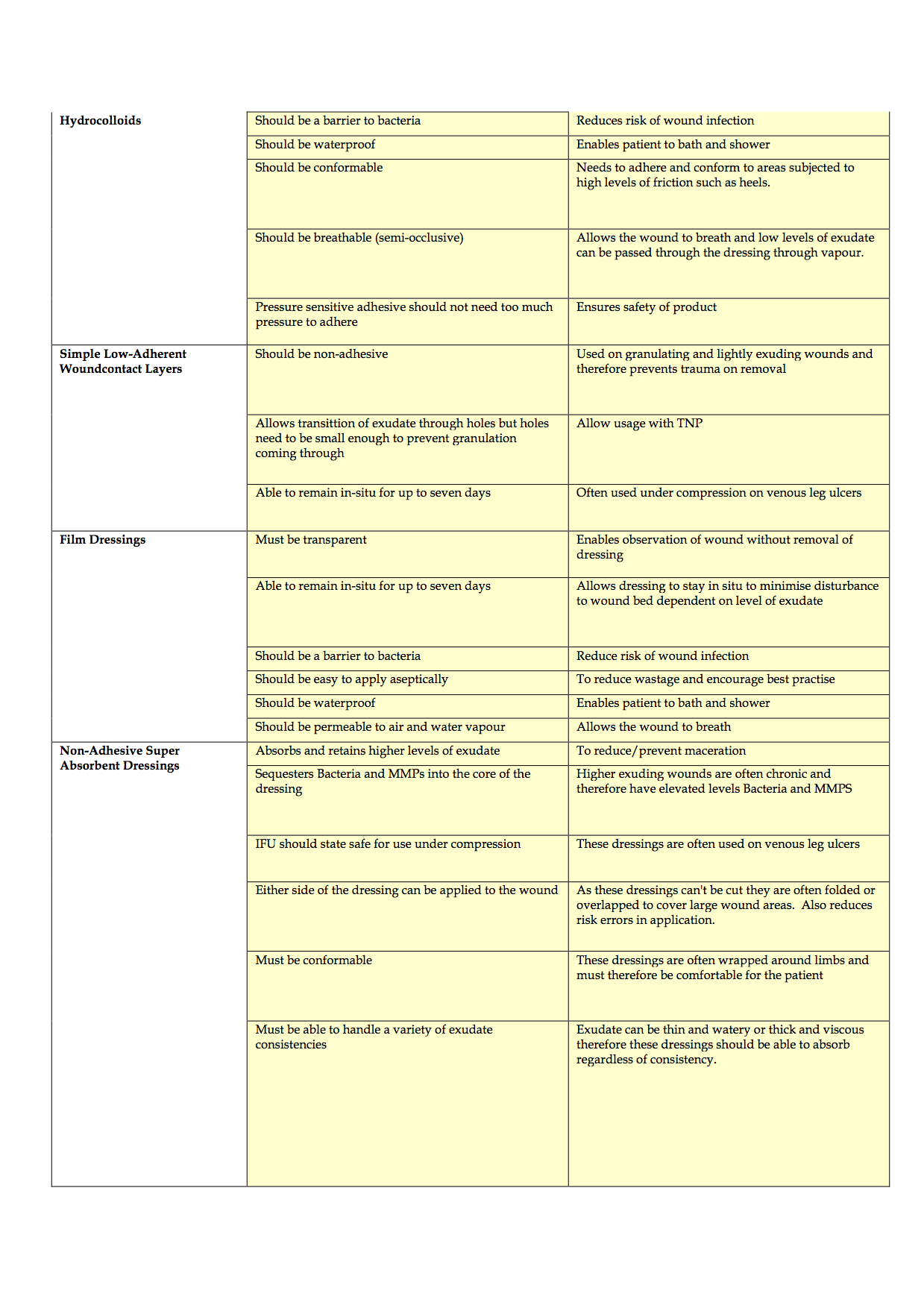

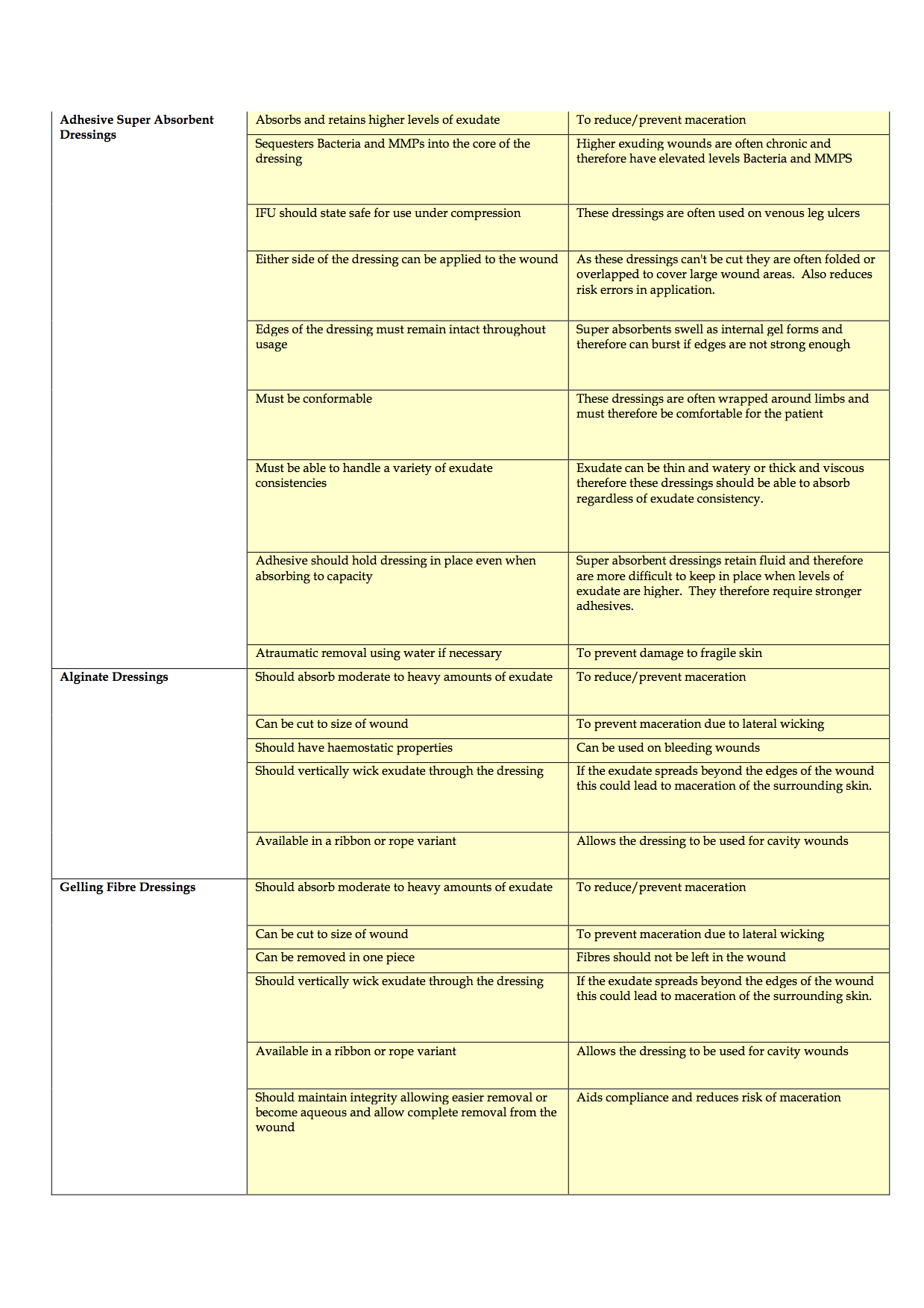

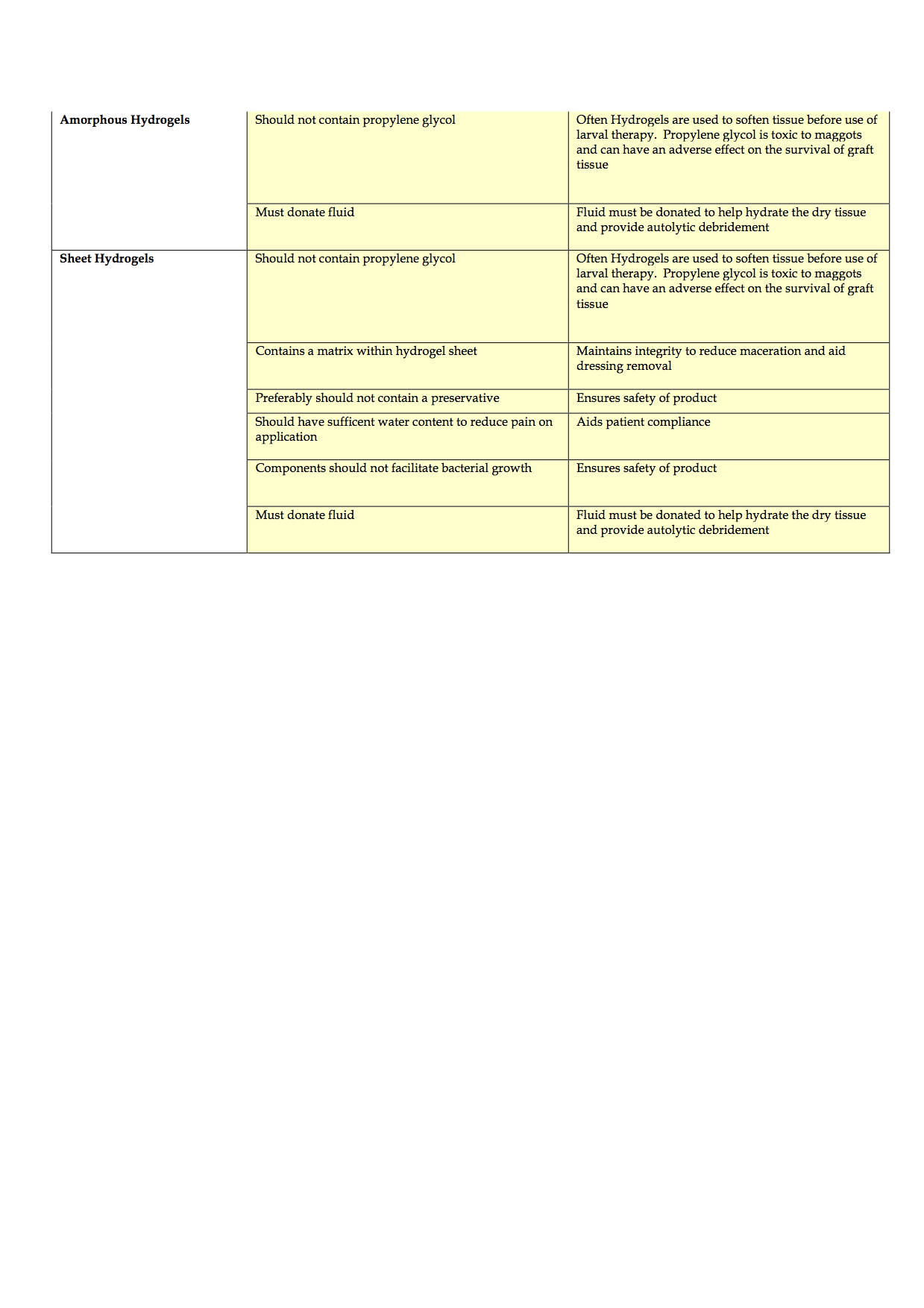

Completion of the criteria has been challenging and is ongoing, due, in part to the time delays in completing effective evaluations of products to consider for inclusion and staff shortages. To date, the authors have discussed the product categories to include, agreed the criteria of qualities that dressings should possess and agreed that potential rebates and the level of support that companies can provide in terms of education and support also need to be considered. The generic criteria are shown in Appendices 1-4.

Discussion

The authors discussed that the top five products within each category that met both the quality criteria set and pricing requirements would be short-listed for evaluation for potential inclusion onto their formularies and that further discussions would take place following the evaluations with procurement to ensure cost effectiveness in light of potential rebates available and clinical support also available from suppliers selected for shortlist.

So how might using these criteria save time and resources? Within the NHS there are [3]:

- 155 acute trusts

- 56 mental health trusts

- 34 community providers

- 10 ambulance trusts

- c.8,000 GP practices

- 209 clinical commissioning groups

That adds up to 8,464 organisations. Realistically, some won’t have a formulary and some will share formularies. So, if for argument sake, we take off two thousand, we can calculate some approximate figures:

- 6,464 organisations with an average of four professionals in the wound formulary group (WFG)

- WFG meet four times per year for 2 hours (4x4x2)

= 36 hours pa

That equates to 232,700 hours spent on formulary reviews per annum.

In the UK, in the period from December 2012 to December 2013, NHS spend on advanced dressings was been in the region of £187 million [4] and £37,377,221 on general wound care products (films, non-woven dressings etc). Wound dressings account for about £120m of prescribing costs in primary care in England each year [5], although more recent figures suggest that the total annual dressing spend is £302m; £130m (43%) through NHS Supply Chain and 57% via direct purchase or FP10 (personal communication).

The cost of the dressing will vary according to the manufacturing company (the price of dressings within the same category between companies) and/or any local ‘agreements’ with an organisation. For example, rebate discounts may be offered if x amount of the dressing are used per annum, or if another product from the same company is also on WCF. Procurement teams also influence the cost to the organisation, particularly if they are able to bulk buy for several organisations.

National picture

Nationally, comparative wound management product data has demonstrated that NHS Supply Chain customers have saved £2.4m [6]. The NHS Supply Chain’s (NHSSC) Clinical Reference Board (CRB) has begun work with Department of Health to develop national generic specifications, classed as “good enough” and “fit for purpose”, for wound care products [6]. These will be written by the National Wound Care Formulary Working Group [6], supported by sub-groups which will include TVNs, burns management and infection control nurses, and medicine management practitioners. The main objective of the project is stated to ensure that the vast majority of wounds (80% by value) are treated by products meeting these specifications. The intention is to make short-term cost saving on the purchase price of wound dressings – with a target of £13.2m [7].

Seven wound care and dressing lines, representing about 80% of wound dressings, are being considered. These include:

- Films

- Super absorbents

- Non-woven island dressings

- Barrier creams & ointments

- Foams and specialist foams

- Wound contact layers

- Gelling fibres

By setting such generic standards, the CRB suggests a potential to deliver 10–20% savings for NHS providers [6].

While this national formulary sounds like a simple solution, a number of issues require consideration. While it is out-with the scope of this paper to explore these in details, they are briefly summarised in Box 1.

Fletcher et al [8] suggest that due to the speed of the proposed programme, only written specifications rather than proper evaluations may result and that tissue viability nurses and others professionals should perhaps use this opportunity to explore alternatives. This is what the authors have done.

Conclusion

The authors recognise the need for a rationalisation of formularies to achieve national consistency and cost savings and welcome the implementation of the National Wound Care Formulary Working Group who will hopefully achieve this aim while protecting the autonomy that tissue viability teams have in making independent evidence based product selection for their formularies.

Collaborative working between procurement and clinicians will improve the way that Trusts evaluate total treatment costs, i.e. wear time, length of stay etc and supplier support offered, rather than simply considering unit costs in isolation. Tissue viability nurses have the evidence based clinical knowledge that the procurement team do not, therefore it is critical that they are consulted on which dressings are procured by their Trust and are able to share their knowledge regarding which companies and products they wish to engage with and evaluate. Procurement can facilitate this process further by informing TVNs of all market participants and any new innovation in the supply market; in addition, procurement can lead commercial negotiations with the selected suppliers to ensure the Trust obtains the best possible price either by driving down unit costs or obtaining rebate commitment deals.

The authors believe that this alternative approach, focusing on a clinical/commercial partnership, delivers the best outcome for a Trust and its patients as tissue viability nurses and procurement staff are in a unique position to streamline formulary development and reduce costs. The development of their criteria shows that the points to consider when reviewing a formulary can be addressed, and that dressing selection can be cost effective and flexible, allowing practitioners to use their clinical judgement and tailor the dressing regimen to the patients’ individual needs, without being restricted by being to ‘good enough’ or merely ‘fit for purpose’ dressings.

Editors note:

The work that the authors have undertaken dovetails with the work currently being undertaken on the development of a suggested national wound formulary. Indeed, it has been seen by a member of the working group who is taking it to them for consideration for use in their processes.