Lymphoedema Explained

International Lymphoedema Framework Team

Introduction

Lymphoedema is frequently misunderstood and thus mismanaged. This article, taken from the document ‘Best Practice For the Management of Lymphoedema – 2nd Edition: Surgical Intervention – A position document on surgery for lymphoedema’, outlines the causes of this disease, its classification and progression, and the signs to be aware of.

The lymphatic system is part of the circulatory system; it maintains the flow of fluids around the body while removing and transporting waste products from tissues [1]. Under normal conditions, venous capillaries reabsorb 90% of the fluid in the tissues, and lymphatic channels absorb the remaining 10% of lymph fluid, proteins and other molecules [2]. Lymphatic fluid passes to regional lymph nodes and empties into the venous system, most commonly by way of the thoracic duct. Lymphoedema is an external or internal manifestation of lymphatic insufficiency and deranged lymph transport [3]. This insufficiency causes an accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid, leading to distention, proliferation of fatty tissue and progressive fibrosis. Skin changes such as thickening and hair loss may occur, and eventually, significant disfigurement and loss of function. Lymphoedema manifests as swelling of one or more limbs and may include the corresponding quadrant of the trunk. The head and neck, breast or genitalia may also be affected. Significant functional and psychological morbidity, such as disfigurement, pain and complications results from end-stage sequelae of lymphoedema [4,5].

Lymphoedema is generally classed as either primary (hereditary), related to congenital malformation of the lymphatic channels, or secondary, resulting from disruption to the lymphatic system.

Primary lymphoedema

Primary lymphoedema represents a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes sporadic, hereditary and syndrome-associated forms. The estimated prevalence of primary lymphoedema is 1.15 in 100,000 persons under the age of 20 [6]. In children, the two main causes are Milroy disease and lymphoedema distichiasis [3].

Secondary lymphoedema

Secondary lymphoedema is a consequence of removal or damage to lymph nodes, fibrosis of the nodes (post-radiotherapy), and trauma or infection [7]. Side effects of advanced diseases such as cancer, chronic heart failure, neurological and liver disease, and end-stage renal disease can cause chronic oedema. An increase in the bariatric population has seen an increase in lymphoedema, although filarial disease, transmitted by mosquitoes, remains the most common cause of lymphoedema worldwide. The term ‘chronic oedema’ has been adopted by European investigators to define a population of patients with long-standing oedema ( 3 months), and perhaps a more complex underlying aetiology. Prevalence estimates for chronic oedema are between 1.3 and 1.5 per thousand [8].

Classification of the causes of secondary lymphoedema

There is a lack of consensus regarding the causes of secondary lymphoedema. In the United Kingdom (UK), the classification of causes comprises [9]:

- trauma and tissue damage (for example, burns, lymph

- node excision, radiotherapy, varicose vein surgery)

- malignant disease/treatment (lymph node metastases/

- excision, infiltrative carcinoma, lymphoma, radiotherapy,

- pressure from large tumours)

- venous disease (chronic venous insuffi ciency, venous

- ulceration, post-thrombotic syndrome, intravenous drug use)

- infection (cellulitis/erysipelas, lymphadenitis [inflammation

- of the lymph nodes], filiaris, tuberculosis)

- inflammation (rheumatoid arthritis, dermatitis, psoriasis,

- sarcoidosis, dermatosis with epidermal involvement)

- endocrine disease (pre-tibila myxoedema)

- immobility and dependency (dependency oedema, paralysis)

- factitious (self harm)

Stages of lymphoedema

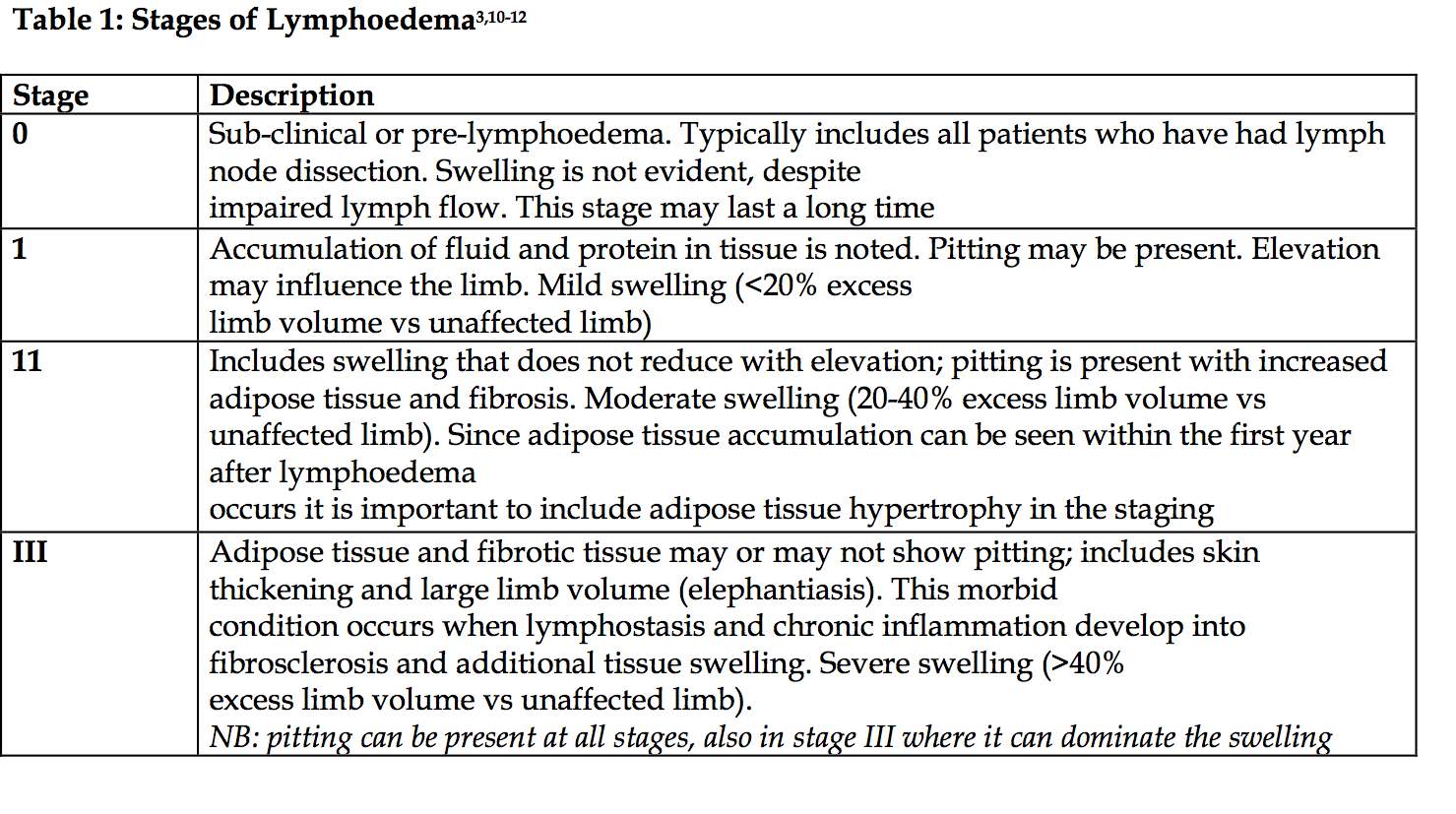

Lymphoedema presents in stages (Table 1); each stage may have a negative impact upon quality of life and possibly, due to recurrent tissue infection, disfigurement, pain, and impaired mobility, lead to social isolation.

Early signs of lymphoedema

Both primary lymphoedema and lymphoedema associated with non-cancer secondary causes, may initially present post-surgery as swelling, discomfort and inflammation; sensations of heaviness, tingling and aching also have been reported [13].

Both patients and practitoners need to be aware of these signs and symptoms:

- clothing or jewellery, e.g. sleeve, shoe or ring, becoming tighter

- feeling of heaviness, tightness, fullness or stiffness, and/or pain

- aching

- observable swelling

- tissue swelling – mild, moderate or severe; pitting or non-pitting

- skin condition – thickened, warty, bumpy, blistered, lymphorrhoeic, broken or ulcerated

- subcutaneous tissue changes – fatty/rubbery, non-pitting or hard

- shape change – normal or distorted

- frequency of cellulitis/erysipelas

- associated complications of internal organs, for example,

- pleural fluid, chylous ascites (accumulation of chyle in the

- abdominal cavity)

- movement and function – impairment of limb or general function

- psychosocial morbidity

Lymphoedema is frequently misunderstood and thus mismanaged